Prohibition does little to impact supply and demand

Five things to consider before expanding your cannabis retail business

February 18, 2025

The Game-Changing Data Platform for the Cannabis Industry

March 8, 2025The goals of cannabis prohibition in addressing supply and demand are to 1) eliminate the availability of cannabis by punishing those who sell it with jail time and economic and social sanctions and 2) discourage cannabis consumption by making possession illegal and attaching sanctions to being a known consumer (e.g. child custody, employment, college funding). The modern era of cannabis prohibition began in the 1970’s with the passage of the Controlled Substances Act and ramped up in the 1980’s and 90’s through a militarized strategy against drug users and sellers. Since that era, the number of people in the United States incarcerated for drug related crimes has ballooned, making the US the top jailer in the world in terms of population density. Cannabis prohibition has succeeded in tearing apart families, preventing patients from accessing a vital medicine, taking away opportunities for economic stability and costing US taxpayers billions of dollars. What it has NOT done, is stifle the supply and demand for cannabis in the United States.

The argument in favor of prohibition over the years has focused on the need to keep cannabis illegal to prevent widespread use. But, has prohibition done that? Are consumers in medical only states with the lowest consumer density different than consumers in adult use states with the highest density? Does prohibition really stifle supply and demand? Or does it simply impact a person’s willingness to admit that they are a cannabis consumer?

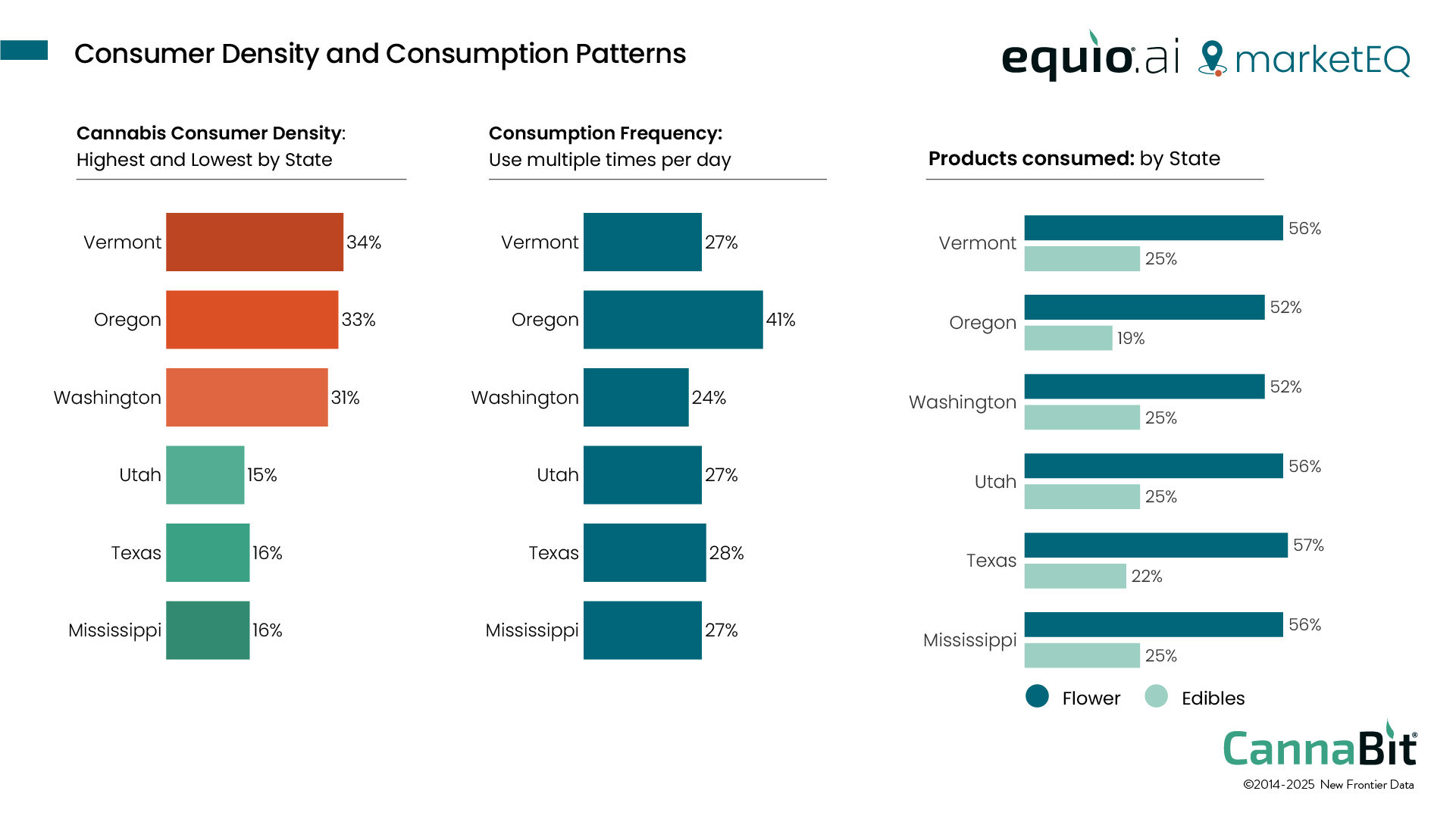

To explore these questions, we looked at cannabis consumer density in the adult use states with the most consumers per 1000 adults and the medical only states with the fewest consumers per 1000 adults from the New Frontier Data platform marketEQ. We compared the % of consumers who report using cannabis multiple times per day, and the methods they use to consume. Data show that even though density may differ, likely due to willingness to admit use, regular consumption and product forms do not. This suggests that stricter cannabis policies are associated with fewer people identifying as consumers, but not with consumption frequency or methods of ingestion.

Consumer Density

Among states that have passed adult use cannabis laws, Vermont, Oregon and Washington have the highest level of consumer density. Thirty-four percent of Vermont, 33% of Oregon, and 31% of Washington adults say they are cannabis consumers. Among states that have only medical cannabis access, the lowest density is in Utah (15%), Texas (16%), and Mississippi (16%). These states have medical laws, but still restrict access based on medical condition and do not have all medical cannabis products available.

Utah, Texas, and Mississippi have traditionally had some of the toughest state cannabis laws in the country. In these states, simple possession can result in jail time and a fine, while selling of any amount is considered a felony. In Texas, for example, possession of less than one gram of concentrate is a felony with a mandatory minimum sentence of 180 days in jail and a fine of $10K (www.norml.org).

It is easy to see why people in those states, unless protected by medical cannabis status, would be hesitant to admit that they are cannabis consumers. But do differences in the law extend to differences in consumption frequency or products used? In other words, prohibition-style policies may impact disclosure, but do they impact supply and demand? No.

Data on consumption frequency reveals that consumers in low-density states are just as likely to report using cannabis multiple times per day as consumers in high-density states (except for Oregon, where consumers report higher-than-average consumption frequency). In high-density states, multiple times per day consumption ranges from 24%-27% of consumers. In low-density states, it ranges from 27%-28% of consumers. There are no differences in product forms used either. While prohibition is designed to curb supply, consumers in high-density states report similar rates of flower and edible use as low-density states. For the high-density states, flower use ranges from 52%-56% and edible use from 19%-25%. In low-density states, flower use ranges from 56%-57% and edible use from 22%-25%.

Most, if not all US states seem to be moving away from prohibition as a policy approach. Even states where prohibition has been deeply engrained like Indiana and South Carolina are considering allowing medical access. The shift we have been seeing since 1996 acknowledges that prohibition has failed at curbing supply and demand. It supports a more rational and public health-based approach. The data supports that the fear of legalization resulting in vastly different supply and demand paradigms has been unfounded. To look deeper into this and other retail, consumer and market data, sign up for FREE access to marketEQ.