Cannabis vs. COVID Study Illustrates U.S. Need for Key Research

California Tax Rates Impede Legal Operators

January 18, 2022

An Industry in ‘Bloom’: New Frontier Data Analysts Discuss What’s Coming in 2022

February 1, 2022By J.J. McCoy, Senior Managing Editor, New Frontier Data

As culture wars are raging in the United States about COVID-19, masks, vaccinations, etc., the politicization of science and substances like cannabis becomes sensational, making it more difficult to separate fact from fiction.

This month alone, there have been widespread news reports that erroneously interpreted findings published January 10 by Oregon State University researchers in the Journal of Natural Products.

With headlines like “Cannabis Compounds Stopped COVID Virus from Infecting Human Cells in Lab Study”, and “Compounds in Cannabis Show Promise as a Treatment for Coronavirus Infections”, the prospects of cannabis offering protection from COVID-19 quickly went viral, aided by abbreviated, Twitter-shortened headlines that largely missed vital nuances of the science.

Mainstream coverage of the findings provoked overreach about the findings, and some consumers flocked to cannabis dispensaries and CBD outlets to buy products in hopes of defending people from COVID-19 infection. While experts urged caution about the findings, the public’s enthusiastic if ill-informed responses prompted jokes from late-night hosts like ABC’s Jimmy Kimmel, who quipped that “all this time we’ve been listening to the CDC, we should’ve been eating CBD.”

Important details commonly missed included the fact that Oregon State University’s in vitro study has not been subjected to human trials, and is not slated to be, since medical cannabis research remains federally limited. Other key takeaways ignored were that cannabigerolic acid (CBGA) and cannabidiolic acid (CBDA) appear in very small quantities in retail cannabis, and are converted to other compounds after decarboxylation and/or smoking. Ergo, smoking would not provide an efficient means for gaining any benefits.

The takeaway? The research does not, in any practical sense, mean that cannabis provides any preventative benefit against COVID-19 in the forms in which it is most commonly consumed.

That noted, the Oregon State study essentially confirms previous evidence that CBDA has medicinal properties. As Inesa Ponomariovaite, CEO of Nesas Hemp, told High Times, “the big takeaway from this study however, is that the compounds that help prevent the virus that causes COVID-19 from entering human cells are [CBGA or CBDA, but] not the generic CBD compounds that are found in so many hemp products today,” she said.

As Dr. Reggie Gaudino, VP Research & Development for Front Range Biosciences (and New Frontier Data’s Chief Science Adviser), reminded, previous research had suggested some potential for CBD to block the coronavirus, but much more study is needed.

“It still has to be investigated like a medication,” he said, “because it will have cross-interactions that potentially cause contraindications: Low doses don’t seem to do much, [while] high doses seem to slow down some drugs’ conversion. That could be a problem. Bottom line: If we want it to be considered a medicine it should be treated like one, and the proper studies done.”

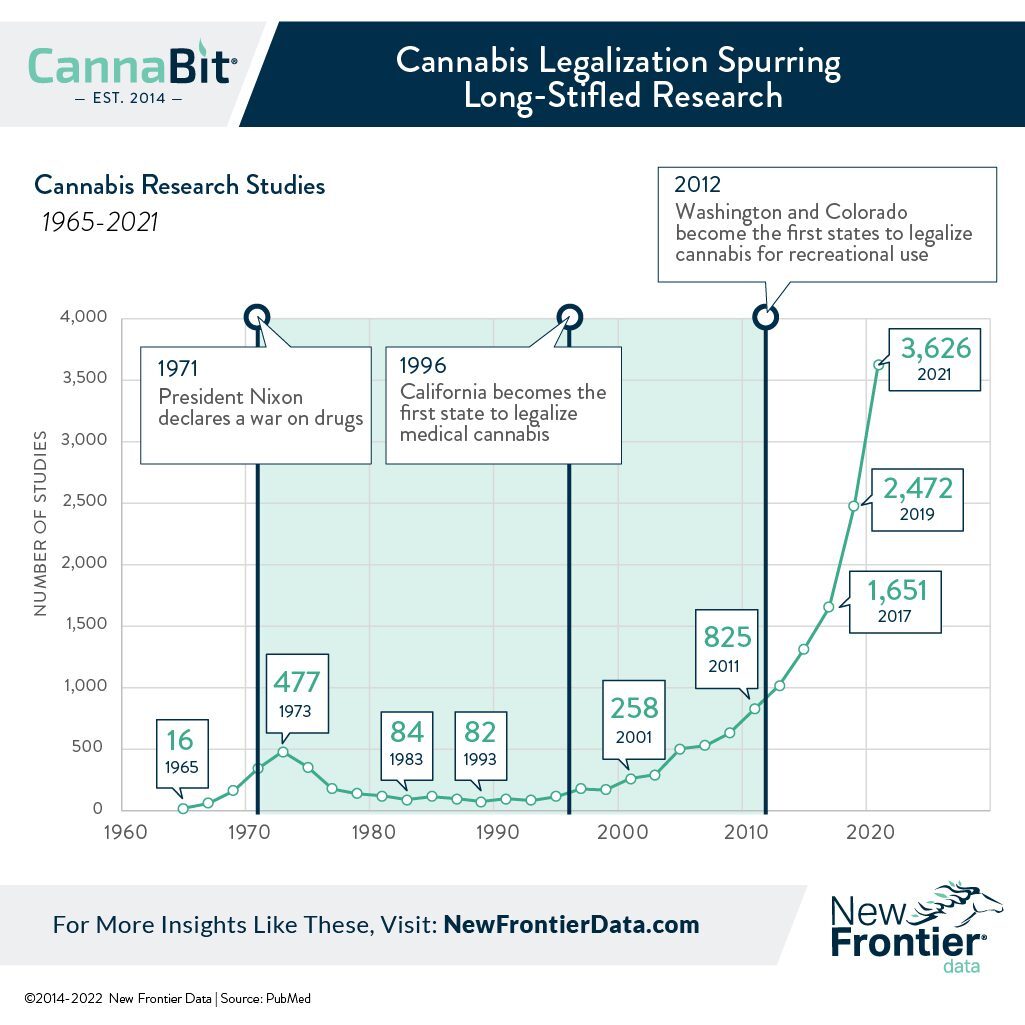

As noted by Amanda Reiman, New Frontier Data’s VP of Public Policy Research, the fallout from the study and responses also illustrates how far the legal cannabis industry has to go in catching up after lost opportunities during U.S. prohibition of the plant. New Frontier Data addressed part of the issue in its report, Up in Smoke: Analysis of the Cannabis Administration & Opportunity Act, noting examples of how the U.S. federal government has served as an impediment to research, and citing the industry’s needs for fair and equitable oversight.

“Research has been stifled for decades because the government’s refusal to take cannabis seriously as a medicine,” Reiman said. “If we had started research on cannabis in the 1930s, think how far we would be with developing cannabinoid-based medications. With so much focus given to intoxication from THC and the psychotropic properties in cannabis, we keep missing the benefits from other cannabinoids. The inability through federal prohibition to do research on cannabis has stifled potentially groundbreaking discoveries, like the study’s hypothesized application against COVID-19. What else could we have used cannabis for? Will findings like these finally impact the government’s willingness to look at cannabis realistically?”

Last June, the Supreme Court refused to hear arguments in a May 2020 lawsuit filed by a group of scientists and veterans in an effort claiming that the federal classification of marijuana as a Schedule 1 drug under the Controlled Substances Act is unconstitutional based on the plant’s possible medical uses.

The move disappointed advocates who had hoped that a positive decision would compel the DEA to reschedule the plant. Now the likelier eventuality is that the U.S. Congress will either reschedule or deschedule marijuana.

Adding to the impediments for advancing cutting-edge science is that researchers have been limited to using cannabis products supplied to the National Institute on Drug Abuse by the University of Mississippi, which researchers have long described as substandard, bearing little resemblance to cannabis currently available in legal markets.

Any company seeking to study and test cannabis products for human use is first required to gain FDA approval, after permission from the Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA). Last year, the DEA finally eased some longtime restrictions when it awarded two private firms with contracts to produce cannabis for federally funded research, a development which National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) Director Nora Volkow reportedly welcomed as “valuable” for U.S. researchers to access in better understanding the risks and benefits of cannabis and products consumed across the country.

As Ripple cofounder and CEO Justin Singer shared in a recent essay, “marijuana’s Schedule-I status doesn’t make it impossible to conduct human trials — just ridiculously difficult and expensive… The FDA should be pushing for more research to keep consumers safe, and instead companies such as mine have to do it on their own at great expense even though there are plenty of university scientists who would gladly put grant funding to work on the project. The federal government hasn’t gotten out of the way; it’s just become a more dissembling roadblock.”

Other countries have been more active and progressive. Israeli organic chemist Raphael Mechoulam, a professor of medicinal chemistry at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, is credited for publishing more than 450 research articles. The “father of cannabis research” is best known for his work studying delta-9 tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) the active psychotropic component in cannabis. A specific study conducted by Mechoulam, a founding member of the International Association for Cannabinoid Medicines, focused on pain and the use of cannabis.

Working with medical cannabis does not require any abandonment of objectivity or skepticism, and mounting evidence being collected worldwide is increasingly affirming the plant’s broad therapeutic potential.

Advocates and scientists argue that for too long, marijuana was preordained by the U.S. government as having “no currently accepted medical use and a high potential for abuse” despite mounting contrary evidence from research being done globally, and from the feedback collected from the millions of patients participating in U.S. state medical cannabis programs.

Absent research to guide the U.S. industry’s regulation, the market for cannabinoid infused products has proliferated — especially since hemp became federally legal — thereby opening a patchwork of markets nationwide for CBD and other non-THC cannabinoids.

Interested shoppers today can find CBD-infused oils, drinks, vitamins, mints, cheeseburgers, shampoos — even clothing – though discerning which products are best suited for each consumers’ intended application is often a challenge due the lack of research and regulatory control. A notable 2017 report in the medical journal JAMA shared the findings of researchers who analyzed 84 CBD products from 31 companies, finding that 69% were mislabeled if not altogether fraudulent, as some products had too much CBD, some too much THC, and some had no CBD at all.

Ultimately, the U.S. government’s lack of recognition of cannabis as a medicine has had deleterious, decades-long impacts on research and discovery. However, with signs that the U.S. may be on the cusp of foundational policy reform, cannabis may soon be officially returned the American pharmacopeia.

As Gaudino summarized, “80-plus years of prohibition has hampered cannabis from being placed back into the medical arsenal where it originally came from — Pliny the Elder spoke about boiled roots of cannabis in 79 A.D. — and the more work we do, the more we find that there may in fact be ‘a cannabis variety for that’.”