Momentum for Federal Legalization of Cannabis Shifts Toward Incrementalism

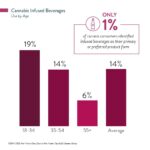

U.S. Consumers Acquiring a Taste for Cannabis-Infused Beverages

May 10, 2022

Cannabis Professionals Offer Cases to Promote SDGs at United Nations

May 17, 2022By J.J. McCoy, Senior Managing Editor, New Frontier Data

In progressive circles, the late Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg was treated like a rock star before she passed in 2020 at age 87. Her fights for gender equality made her an establishment feminist even before President Bill Clinton nominated her to the nation’s highest court in 1993, but she wound up as an improbable pop-culture icon, even featured in an Oscar-nominated documentary film and feted with her own action figure.

Lost to many of her fans amid the hype, however, seems to have been some of the messaging in her approach: “Real change, enduring change, happens one step at a time,” she counseled. “You can’t have it all, all at once.”

If those notions seem quaint in these days of DoorDash and Amazon Prime, they remain important messages for the legal cannabis industry, too. Even while history is being made daily as more states adopt medical and adult-use programs, passions must be pragmatically tempered with patience. Across the country, attitudes toward cannabis are becoming more permissive and accepting, but for the time being partisan gridlock in Congress virtually ensures that currently proposed legislation to decriminalize marijuana will languish and die somewhere buried in the U.S. Senate.

Federal Legalization Deferred

Incrementalism underscores the solution: While there is political hay to be made in talking about cannabis reform, there is vanishingly little being effectively done to pass cannabis reform. And that, unfortunately for many cannabis advocates, is not likely to change soon, especially with national focus being divided by the Russian invasion of Ukraine, tumult over the Supreme Court’s handling of abortion rights, and the midterm elections in six months.

Optimism is found in a broader perspective, notes Amanda Reiman, New Frontier Data’s Vice President of Public Policy Research. “Cannabis legalization used to center around ‘if’ and not ‘how’. ‘If’ was easy to answer – ‘yes’ or ‘no’ – politicians usually came down on the side of ‘no’, save for a few progressive champions. However, now that the question has shifted to ‘how’ there are many varied interests wanting to benefit from whichever regulatory structure is adopted, this makes the discussion of ‘how’ inherently more complicated than the simple of question of whether people should go to jail for cannabis.”

Reiman suggests that “maybe we’ll see banking reform prior to 2025 and we will see other states come on board with medical and adult-use programs. So, the lack of federal law isn’t stopping progress, but it may make the future road to compliance more difficult for state-licensed companies and state-level programs the longer they continue to operate without the overlay of eventual federal requirements.”

House Bills Likely to Stall in Senate

Last month, the U.S. House of Representatives passed the Marijuana Opportunity Reinvestment and Expungement (MORE) Act by a narrow 220-204 margin, mainly along partisan lines. The bill aims to decriminalize cannabis, throw out some old marijuana-related convictions, and allow states to decide for themselves whether to legalize and regulate cannabis for sales and tax revenues. Nevertheless, there is virtually no chance of its becoming law anytime soon. The last time that the House voted to decriminalize cannabis was in 2020, when the Senate refused to consider the bill; such is its probable fate again now.

As was the case two years ago, when New Frontier Data detailed some of the hurdles which have stymied broader federal cannabis reform despite growing public support, the short-term outlook is nil. Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer (D-NY) has been promoting – yet not presenting – his own proposal, the draft Cannabis Administration and Opportunity Act, first announced last year.

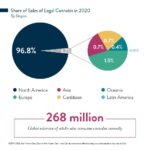

Though Gallup last year found record numbers of Americans (68%) supporting full legalization –a Schedule I drug, federally regarded the same as So while 38 states and the District of Columbia have opted to legalize and regulate the production, sale, and use of cannabis (either for adult or medical uses), they have done so while fully realizing that they remain at odds with federal law.

Cannabis was designated a Schedule I criminal substance more than a half-century ago by the Nixon administration, defined by “high potential for abuse and no currently accepted medical uses”. According to the National Center for Drug Abuse Statistics, the U.S. government spends $33 billion annually prosecuting the war on drugs. Additionally, efforts concerning the enforcement of cannabis prohibition have often disproportionally targeted minority communities.

In addition to descheduling cannabis, the MORE Act would require federal courts to purge convictions for cannabis-related offenses and allow re-sentencing for individuals with federal convictions. It includes funding for social equity programs in communities that have been hurt most by enforcement of old drug laws.

So why does the political kabuki continue? Gallup’s numbers indicate that while 83% of Democrats support legalization, so too do half (50%) of Republicans, with support notably high among younger Republican voters. Though while there seems to be plenty of political will to pass cannabis reform, there seems to be precious little momentum for it.

Popularity versus Politics

And there lies the rub: Political caution and a lack of judicial intervention could explain why cannabis legalization has not kept pace with public opinion. Movements tend to be driven by the lobbying of policymakers, mass protests that raise awareness, or ballot initiatives (though only 26 states provide for those).

Though it is possible that politicians will eventually champion the issue with more conviction, their tendency is not to get out front.

“Is it a good idea? Is it a safe issue politically?” mused Grover Norquist, president of the conservative libertarian lobby Americans for Tax Reform, in describing the calculus during last month’s National Cannabis Policy Summit in Washington, D.C. “I think that most officials recognize it’s safe,” he said. “The polling data has moved some, but with what intensity?”

“Taking some of the steps knocks down the arguments,” Norquist continued. “Why then don’t we pass these bills? Bills that everyone likes do not become laws, but hostages: They take a good idea, but with all of the anchors it slows everything down. The votes are there for 280e, state by state. The regulations for cannabis are worse than for alcohol, and that’s hard to do.”

“There is a ‘cost to doing things’ going on,” he concluded, noting that – as Justice Ginsburg advised – an all-or-nothing approach tends to yield more of the latter than the former: “If you want to make steps in politics, you take what you can.”