Civil Protests Give Urgency to Cannabis Industry’s Social Equity Programs

Law Enforcement’s Ill-Gotten Gain: Civil Asset Forfeiture Laws v. Cannabis

June 29, 2020

Lotame and New Frontier Data Partnership Connects Big Brand Advertisers to More Than 100 Million CBD Consumers

July 8, 2020By Noah Tomares, Research Analyst, New Frontier Data

What is a Social Equity Program?

While traditional American rhetoric offers a great deal about equality, there is comparatively little mention of equity. In business, equity often refers to shares in or ownership of an organization. The Cannabis Control Commission of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, however, defines it as “the recognition and accommodation of differences to prevent the continuation of an inequitable status quo”. Social Equity Programs (SEPs) are focused initiatives designed to address inequality in the national cannabis market by incorporating both interpretations.

Inequitable Status Quo

The United States has seen a significant ideological shift about cannabis. The latest Gallup poll found 70% of Americans believing smoking cannabis to be “morally acceptable.” In a national pandemic, cannabis businesses nationwide have been declared essential businesses; in some states, cannabis has gone from the “Devil’s Lettuce” to a hip new ingredient featured on modern cooking shows.

Law enforcement remains relatively unaffected by the public’s attitude. Ever since President Nixon’s 1971 declaration of a “war on drugs” and the designation of cannabis as a Schedule I drug (deemed illegal due to presenting high risks for abuse without any viable medical use), the U.S. government has lavishly dedicated tax dollars to federal drug control agencies. A 2015 report estimated $9.2 million being spent daily (and $3.3 billion annually) to incarcerate people in federal facilities for drug-related offenses. According to the Drug Policy Alliance, 663,367 people were arrested for marijuana violations in 2018 — roughly one arrest per every 48 seconds. In 2019, just under $30 billion was spent on drug control.

Enforcement of such laws has always been disproportionately severe for minorities. A national report from the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), found that black people are 3.64 times more likely than are whites to be arrested for marijuana possession, despite comparable usage rates. In some states — such as Montana (9.62x) and Kentucky (9.36x) — the ratios are significantly higher.

Recognition and Accommodation

SEPs are intended to address injustices both historic and contemporary while tackling a range of social and economic issues. Models for recompense can take many forms as individual states or cities design and enact their own initiatives.

The City of Los Angeles, for example, notes that its SEP endeavors to “promote equitable ownership and employment opportunities in the cannabis industry in order to decrease disparities in life outcomes for marginalized communities, and to address the disproportionate impacts of the War on Drugs in those communities.”

L.A. offers priority application processing and business support to individuals who have been disproportionately impacted by the previous criminalization of cannabis activities. Applicants eligible for the program can have their applications and renewals processed on a priority basis. The program has three tiers:

- A Tier 1 applicant must be a low-income individual living in an officially designated disproportionately impacted area (DIA) or have a California criminal record predating November 2016. Applicants must also own at least 51% of the business. Those qualified are granted expedited applications and renewal processing, assistance with compliance and licensing, fee deferrals, and potential access to investment opportunities.

- Tier 2 applicants must be low-income, living in a DIA for at least 5 years (or for 10 years if they are not low-income) and own at least 33% of the business. Qualifying individuals are granted express licensing and compliance support.

- Tier 3 is designed for businesses which will support the permitting process for tiers 1 and 2. Businesses qualifying for Tier 3 must each provide a Tier 1 applicant with access to property, but are rewarded with expedited applications and renewal process permitting.

Massachusetts’ Cannabis Control Commission has its own SEP. Like California, the Massachusetts SEP focuses on communities living in an area of disproportionate impact (DIA). The program’s self-stated goal is to improve the quality of life in such areas by “reducing barriers to entry in the commercial cannabis industry, providing professional training, technical services, and mentoring for those facing systemic barriers, and to promoting sustainable, socially, and economically reparative practices in the commercial adult-use marijuana industry.”

In order to qualify, an individual must have resided in a DIA for at least five of the previous 10 years, been convicted of a drug offense in the last 12 months, or been married to or the child of a person with a drug conviction in the last year. No individual whose income exceeds 400% of the federal poverty level may qualify.

Colorado recently approved new social equity legislation empowering Governor Jared Polis to pardon people convicted of marijuana possession. Nevada has likewise introduced a resolution making tens of thousands of residents previously convicted of low-level marijuana possession eligible for blanket pardons.

The Best of Intentions

Some initiatives have encountered difficulty. In Ohio, after H.B. 523 required the Department of Commerce and the Board of Pharmacy to issue no less than 15% of all licenses to members of economically disadvantaged groups, a central Ohio court subsequently ruled it unconstitutional.

L.A. is contending with potential fallout from proposed overhauls of its SEP. Its Department of Cannabis Regulation recommended granting temporary approval for all social equity license applicants, allowing applicants and businesses to relocate within the city, limiting new storefront retail licenses and delivery licenses to social equity applicants until 2025, and improving processes to minimize predatory practices in its SEP. While many support those recommendations, others have argued that they unduly limit the ability of other applicants to enter the market via legal channels.

Addressing a Need

Despite challenges, SEPs address an undeniable disparity, even in relatively established and mature markets. In Colorado, for example, black people are only 1.54x as likely to be arrested for marijuana as compared to the 3.64x national average.

Denver has identified several social equity initiatives including: continued use of marijuana tax revenue to support low and moderate-income neighborhoods; vacating low-level marijuana convictions; obtaining data related to the marijuana industry; and identifying areas of need in workforce development, licensing ownership, and entrepreneurship.

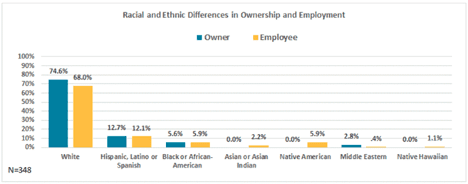

In 2019, a reported 80.8% of Denver’s population identified as white or mostly white, 29.7% as Latino, 9.8% as black, and 4.4% as Asian (multiple options could be selected). Yet, a recent study from the Denver Department of Excise and Licenses noted that minority ownership and employment of cannabis businesses falls quite short, as three-quarters of all local marijuana busines owners identify as white. Employee demographics were slightly more diverse, with 68% identifying as white.

Source: Denver Department of Excise and Licenses

On New Frontier Data’s weekly Cannaweek podcast, Roz McCarthy founder and CEO of Minorities for Medical Marijuana — noted that however well-intentioned, the programs have been flawed.

Among significant challenges faced by those interested in entering the cannabis industry is the cost. While the early stages of the industry may have been less capital-intensive, current regulatory, legal, and compliance costs have risen significantly long before any efforts for building effective products and branding.

SEP participants are simultaneously tasked with learning the nuances of the process along with juggling myriad considerations required in identifying one’s niche in the market and building a business. In such a fast-moving, dynamic space, potential entrepreneurs are often left a step behind their privileged peers.

If the ultimate goal of these programs is equity, additional consideration may be required to ensure that all applicants, regardless of status, are able to enter the market with equal opportunity. For those issues to be addressed long-term, a regulatory foundation needs to prioritize inclusivity and equity, with execution to deliver on those best of intentions.