Digesting the U.K.’s Guidelines for Ingestible CBD, and Impacts for the Industry

U.K. Favorite CBD Product Type (Among CBD Consumers)

February 23, 2020

U.S. Demand for Smuggled Cannabis Plummets as Legal Markets Grow

March 1, 2020By Molly McCann, Senior Manager, Industry Analytics, New Frontier Data

This month, the U.K.’s Food Standards Agency (FSA) forged a path toward regulatory compliance standards for ingestible CBD extract products; as the first governmental body to do so, its guidelines and pace seem destined to serve as an international model which other nations will either emulate or detour from.

The FSA is mandating that by March 31, 2021, CBD businesses will need to have submitted — and received validation for — novel food authorization applications for any ingestible CBD products or see them pulled from market shelves. The practical effect is to place the burden for product safety on CBD producers to demonstrate the harmlessness of their goods through a costly and involved process which many producers will be unlikely to fulfill if more for practical concerns than abundance of caution.

For now, until next April, existing CBD products may be sold given that they are safe, correctly labeled, and do not contain any substances classified as drugs. CBD industry associations have generally responded positively to the statement, appreciating the clarity of the guidance.

The FSA has meanwhile issued consumer guidance suggesting a maximum daily intake of 70 mg of CBD for individuals, while advising pregnant or breastfeeding women and people taking other medications against any use of CBD unless under medical direction.

Among some key near- and medium-term implications of the FSA’s announcement:

Most current CBD companies are unlikely to survive past March of next year with their current offerings.

Compiling the scientific dossier necessary for the novel foods application will be difficult or impossible for many current CBD producers, especially smaller operations. The application is a costly process, requires significant technical expertise, and is not unlike applying for approval of a medicine.

CBD had been leveraged by many speculators as an easy means of ingress to the cannabis industry, with seemingly low barriers to entry. A significant amount of such companies that came to CBD through that strategy (especially the smaller shops among them), are unlikely to fulfill the deadline.

Yet, for those relatively few who will be able to receive validation for their products, potentially very significant growth looms ahead, whether for marketers peddling products to consumers, or for manufacturers of finished food and beverage products who will not need to separately apply for novel food authorization if sourcing from suppliers who have themselves submitted verified applications.

Full-spectrum extracts may be regulated out of existence in favor of CBD isolate.

Broad- and full-spectrum extracts may have difficulty getting approved, as most producers are unlikely to have adequate toxicology data for every compound found present in such products. It will be easier to produce safety data for CBD isolate, which could usher in CBD isolate as the standard for oils, capsules, and additives in foods and beverages.

Hemp food products (e.g., cold-pressed oils) are not considered novel foods given their history of use in Europe since before 1997 — only cannabis extracts are subject to the Novel Foods Regulation.

According to a New Frontier Data survey, full-spectrum extracts seem somewhat more popular than CBD isolate among the U.K.’s CBD consumers, with 51% preferring full-spectrum products and 32% preferring CBD isolate. The consumers did not, however, indicate avoiding the product types they did not prefer.

Due to the current nascency of the European market, preferences for isolate or full-spectrum products have not been strongly presented. No more than 11% of the general British population recognized the difference between full-spectrum oil and isolate, and a lack of clarity extended among CBD consumers, too, as while 32% of UK CBD consumers reported knowing the difference, 37% said they were unsure.

CBD companies that cannot survive as oil, food, or beverage producers may choose to pivot to non-ingestible products.

Novel food regulations apply only to ingestible products including foods, beverages, oil/drops/tinctures, and gel capsules. Products like cosmetics or vaporizers remain unaffected by the FSA’s announcement, though respective agencies may otherwise exercise authority to regulate CBD in such products.

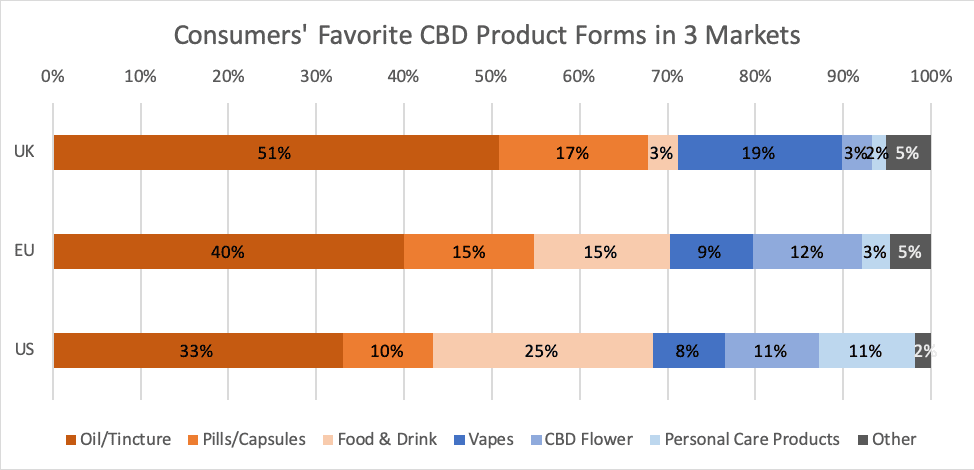

Currently, a majority (71%) of U.K. CBD consumers’ favorite product forms fall into the category for ingestibles. More than half (51%) named oil/tincture as their favorite form, while 17% preferred capsules, and 3% preferred a CBD-infused food or drink. After oil, CBD vaporizers were identified as the next most favorite form, chosen by 19% of consumers. CBD-infused cosmetics and other personal care products reportedly are significantly less popular in the U.K. (only 2% named one as a favorite) than in markets like the U.S., where 11% of CBD consumers reportedly claim a personal care product as their favorite form. The FSA’s announcement may lead existing companies to explore alternative product types, which could eventually boost interest among consumers.

Now that the FSA has stepped forward and offered clear guidance to the industry, it seems predictive for food-regulating bodies of other countries to begin following suit. Whether those regulations will be similar to the FSA’s, they will, at any rate, be influenced by them.

Further European CBD consumer data will be available in New Frontier Data’s upcoming EU CBD Consumer Report: 2020 Segmentation & Archetypes.