Oregon, Going Through Some Growing Pains

Oregon Retail Flower Sales Soar as the Price Per Gram Falls

July 22, 2018

Reducing the Carbon Footprint of Cannabis

July 26, 2018By J.J. McCoy, Senior Managing Editor for New Frontier Data

Oregon has some issues. It has been 20 years since it became (with Washington in 1998, after California in 1996) one of the first states to legalize medical cannabis, and its voters approved an adult-use market in 2014. Oregon knows about cannabis.

It just does not know how much cannabis it has.

Through an internal review released this month, the Oregon Health Authority (OHA) overseeing the Oregon Medical Marijuana Program (OMMP) admitted a lack in regulatory oversight of the industry, particularly concerning growers.

“Potentially erroneous reporting coupled with low reporting compliance makes it difficult to accurately track how much product is in the medical system. This limits OMMP’s ability to successfully identify and address potential diversion,” the report said.

Though the report recognized Oregon’s more than 20,000 medical cultivation sites statewide, it also cited only 58 inspections being carried out in 2017. Meanwhile, the Oregon Liquor Control Commission (OLCC, which regulates the adult-use market) finds itself dealing with an abundance of growers, retailers and edibles producers since the state has no established limits on licensing.

The state provides some cautionary lessons for other states moving toward legalization, and for transforming businesses making the conversion from erstwhile illicit or gray markets to a regulated industry.

Oregon saw a steep drop in medical dispensaries once adult-use shops began opening in 2017: That January, there were 172 dispensaries; by December but 19 remained, as many of the businesses switched to the broader market.

“The results include oversaturation of a market, with falling retail prices,” explains Beau Whitney, senior economist with New Frontier Data. “At a very high level, falling prices are good for consumers: They make products cheaper and highly competitive, which makes product differentiation for consumers. Lower prices, better branding.”

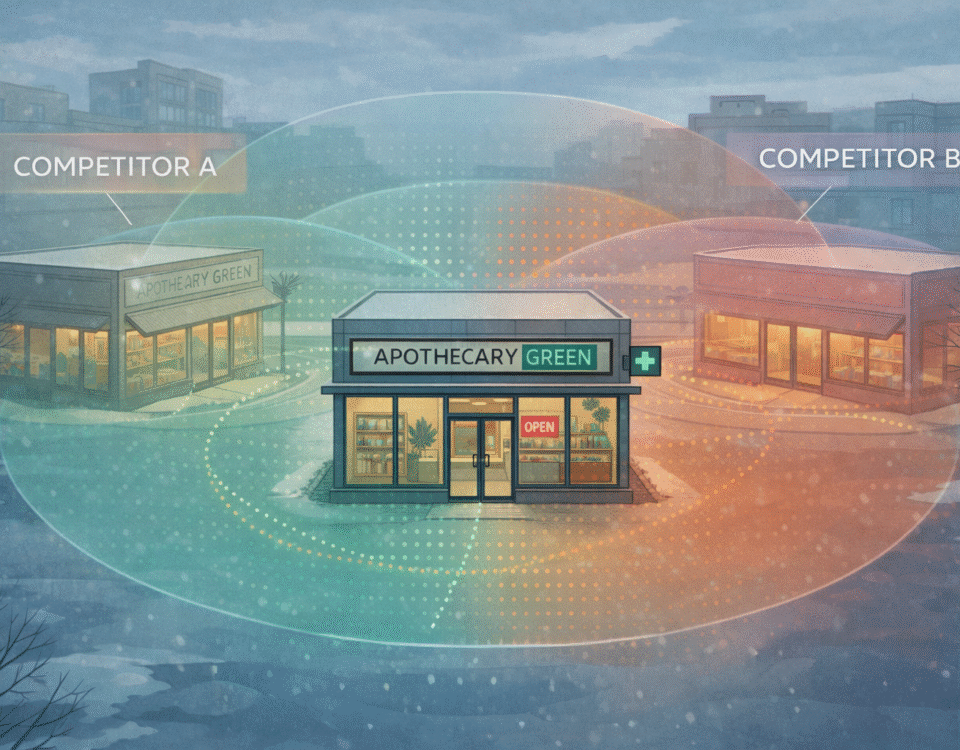

Conversely, he adds, “saturation is bad for suppliers. Everyone and their brother, sister, cousin, and dog are supplying. At some point, people cannot sell at a price under cost. Then they lose money, which drives either their making poor decisions, or simply going out of business. What that also does is drive consolidation. That’s a natural occurrence, but it’s happening right now in Oregon. So, you see the emergence of chains – Chalice, La Mota, and Nectar – and others. Some of these chains are setting up 10, 20 or more retail outlets.”

Per usual, the outlook all depends on positioning. “It depends who you are,” Whitney agrees. “If you’re consumers, it’s great; if you’re operators, it’s bad; but it’s also good for investors. If you’re well-funded and well-capitalized, you can great deals for dirt cheap.”

Whitney expects that it will take another year or 18 months for things to settle in Oregon. Meanwhile another legislative session convenes in January 2019. “They may limit licenses, which helps operators. The takeaway is that it will be a rough ride for operators in Oregon for the next 12-18 months.”

J.J. McCoy

J.J. McCoy is Senior Managing Editor for New Frontier Data. A former staff writer for The Washington Post, he is a career journalist having covered emerging technologies among industries including aviation, satellites, transportation, law enforcement, the Smart Grid and professional sports. He has reported from the White House, the U.S. Senate, three continents and counting.