Amid Raging Wildfires, Is California’s Market Up in Smoke?

U.S. Cannabis Cultivation in California

November 10, 2019

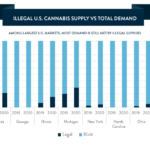

Among Largest U.S. Markets, Most Demand Is Still Met By Illicit Supplies

November 24, 2019By Beau Whitney, Senior Economist, New Frontier Data

With California wildfires seemingly a daily subject in the news media lately, U.S. Department of Agriculture officials have suggested that references to “fire season” should be updated to “fire years” instead. Marked changes in the climate, decreased snows, and more than a decade of drought leave California and other Western states on edge about crises of water resource depletion and perennial wildfires.

Among an annual average of 61,375 human-caused wildfires in the U.S., reports the National Interagency Fire Center, California experiences about 7,500 (12%) of them. Its outsized reputation for them is due to its disproportionate risks from natural environmental features and a population of nearly 40 million, far greater than other Western states or Alaska, which as of last week had fires across more than 2.5 million acres in 2019, compared to less than 300,000 acres in California.

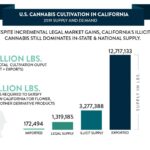

Those wildfires across California unavoidably impact several agricultural industries, cannabis among them. An analysis in New Frontier Data’s new release, “The U.S. Cannabis Cultivation Report: 2019 National and State Output” examines both illicit and legal cultivation, and includes the volume either exported or imported for a given state. In California, the numbers are notably significant in a state with 4.8 million pounds of demand (i.e., the total amount of harvested material required to fulfill all cannabis consumers of flower, oil, or other cannabis product).

In terms of supply, California grows 1.3 million pounds for the legal market, and an additional 3.3 million pounds for the illicit market (with a small amount of supply imported from places such as Oregon or Hawaii). California also grows and exports approximately 12.3 million pounds to state markets across the U.S.

New Frontier Data’s Senior Economist Beau Whitney explained wildfires’ rippling effects. “Given the dominance of the California cultivation industry and its influence over the entire U.S. market, the wildfire situation poses a potentially significant impact across the U.S., as it will reduce the overall supply to the market, decreasing revenues for cultivators and potentially increasing prices for consumers.”

Beyond the burns themselves, wildfires produce smoke and ash that can travel airborne for miles and cover outdoor fields, impacting the growth and quality of agricultural products. While some remediation is possible for oils, damage is essentially unavoidable.

For instance, over the past two seasons, Oregon’s outdoor supply impacted by wildfires was mostly allocated to oils rather than being sold on the market. There were reports of the oils having a smoky flavor above and beyond its normal quality, prompting processors to begin marketing fire-affected raw materials as “smoky” to differentiate it. Meantime, cultivators impacted by wildfires in Oregon lost potential revenue as they were unable to sell their output as flower, and instead processed it into oil. California producers are expected to do the same now to try and salvage their margins after the fires are out.

The impacts on cultivators are not limited to smoke damage. Those who would immediately flash-freeze their plants upon harvest have been impacted by California’s power blackouts. Power lost amid the freezing process essentially ruins the plants – along with any profit value they would have in a frozen state.

The impact hits the processing industry, too: Lost capacity and output due to wildfire and power outages reduces the supply in both legal and illicit markets, raising prices in an already overpriced market and creating yet another obstacle to attracting consumers to legal regulated markets.

Is California’s market up in smoke after the wildfires? Not completely, yet they do represent another onerous challenge to establishing its recently legalized market.