Cannabis Conference Abuzz with Anticipation for New York’s Adult-Use Market

Rhode Island’s Pending Legal Cannabis Program Expects to Gain Profitability by Next Summer

June 6, 2022

How Concerning Is Inflation for Cannabis Consumers?

June 10, 2022By J.J. McCoy, Senior Managing Editor, New Frontier Data

CWCB Expo 2022 last week marked one of the largest cannabis industry trade events to convene in New York since the worst waves of the COVID-19 pandemic shutdowns. Held June 2-4 in the Javits Center, the event offered panel discussions about cannabis and hemp, including interactive educational sessions and the standard vendor displays for products and services ranging from rolling papers and CBD-infused wine coolers, to the National Hemp Association and (being so close to Wall Street) financial consulting services.

No one could blame The City That Never Sleeps for being more than antsy after its dealings with shutdowns and given that in March 2021 New York formally legalized adult-use cannabis, the enthusiasm for what should instantly become one of the nation’s largest legal cannabis markets was obvious. After then-Gov. Andrew Cuomo signed the Empire State’s Marihuana Regulation and Taxation Act as one the nation’s most progressive cannabis laws among the now 18 states (and D.C.) to have fully legalized cannabis, momentum has been building toward anticipated rewards after decades of pro-pot advocacy and activism, and all manner of political horse-trading.

The week’s biggest news out of New York was actually announced in Albany, when a bill advanced by the New York Senate would require public health insurance programs to cover medical cannabis expenses, and add that private insurers be allowed to do so.

Passed 53-10, SB S8837, sponsored by Diane Savino (D), now moves to the Assembly, specifically the Ways & Means Committee. The bill would amend state statutes for public health and social services to address out-of-pocket costs to patients, almost always the biggest obstacle for any medical program.

Overall, New Frontier Data projects the U.S. medical cannabis market to grow at an 11% compound annual growth rate through 2025.

If the bill flies, it will certainly be a boon for New York’s patients who are otherwise unable to afford their medical prescriptions and treatments. It will also mark a strike against the illicit market, while immediately adding major mainstream legitimacy and normalization to cannabis as other states adopt similar measures nationwide.

“Usually when a state passes an adult-use law, the medical cannabis population drops,” explained Amanda Reiman, New Frontier Data’s VP of Public Policy Research. “Potentially, this will make New York the first state to see its medical program expand after adopting an adult-use program, and may impact the dynamics of the resident vs. tourist consumer base as well as the economic projections for the adult-use marketplace.”

Though Cuomo’s administration had dragged its feet in setting up any regulatory framework for a potentially multibillion-dollar market, his successor Gov. Kathy Hochul (D) revved up the machine by appointing Tremaine Wright as chair of New York’s Cannabis Control Board, and Christopher Alexander as executive director of the Office of Cannabis Management.

While cannabis industry activists, investors, and legislators applaud any swift progress, concerns nevertheless linger about which companies will open first, whether the aspirational social equity measures will prove effective, and if Wright’s estimated timeline to set up and launch the industry “later this year” will actually undermine legalization amid a rising gray market.

New York’s legacy market is already long well-established, and an active gray market has emerged since Cuomo signed the law. If state officials take too long to establish a legal market, the illicit market could prevail.

The latter half of 2022 will prove pivotal toward answering those questions.

To this point, state officials have expressed intentions to focus on getting the regulated adult-use market up and running, rather than for making any particular priority of helping morph the gray market into the program.

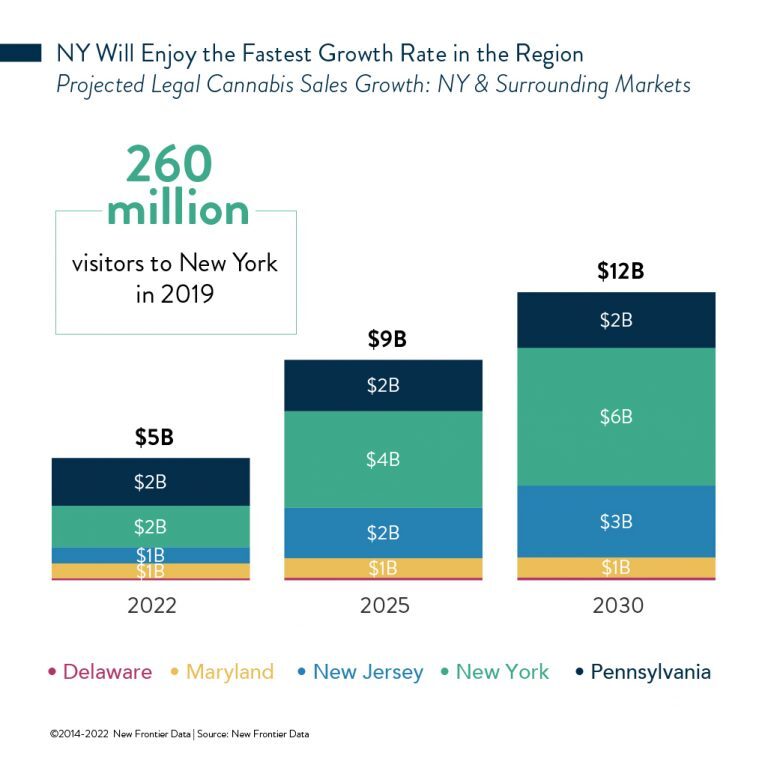

Yet in their “If you build it, they will come” approach, they include ways to crack down on that gray market. And that contradiction suggests a looming problem. Particularly in a state which in 2019 (the last full year before COVID-19 disrupted economies and travel worldwide) drew 260 million visitors.

“We learned in California that this is a mistake,” warns Reiman. “Focusing on standing up the regulated market might work somewhere that did not have an effective, efficient, and formalized gray market prior to legalization (e.g., Illinois, Oklahoma, or Michigan), but New York – just like California – already has a formal and stable gray markets. That means that regulators need to do whatever they can to sway the gray market into compliance via carrots, not sticks. Because in these markets, the gray producers and retailers already have their consumer bases, and are formal and reliable enough that consumers are unlikely to use the new regulated market unless prices are much lower – which we know is unlikely to be the case.”

“On the equity side,” Reiman continued, “they are requiring two years’ experience in running a profitable business in order to be considered for an early equity license. That’s because there is a loan component, and they are trying to vet risk. They are also using this specific measure because others – like credit score – come from a place of bias.”

“Unfortunately, though, running a successful gray market business will not count towards that requirement,” she said. “So, those who have been running successful gray-market businesses in cannabis already have the consumer base (which increases likelihood of success), and are more likely to have been impacted by the drug war because of their business. But they will not qualify for the equity program, and may not be able to get a license.”

As Weedmaps CEO Chris Beals noted during the convention, California has a 70% illicit market rate because of large swaths of unlicensed markets in a state with nearly 40 million residents. What New York should learn from California, the Los Angeles-based entrepreneur said, is “to open up licensing. [Otherwise] your neighbors will, and your local markets will suffer.”

Learning from the example of the Golden State will be vital to a successful legal cannabis market, Reiman cautioned. She stressed how best practices for licensed cannabis businesses vary between states, similarly to how other businesses are variously taxed, regulated, and encouraged, depending on their respective locales.

“Just as importantly as standing up the new program, the state needs to find a mechanism for bringing gray market participants into the regulated space,” Reiman concluded, “and it must be as mindful and compassionate.”